- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 25 August 2025

BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 2911 (2025) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Mental health issues are on the rise, affecting one in seven adolescents. Depression stands out as the most prevalent mood disorder. Enhancing our understanding of adolescent’ perspectives on mental health can improve prevention and promotion efforts. Reviews on mental health of adolescents mainly relied on studies with questionnaires and diagnostic tools. This qualitative systematic review aims to give an overview of the perspectives on mental health expressed by adolescents aged 13–23 in high-income countries on mental health and depression.

Method

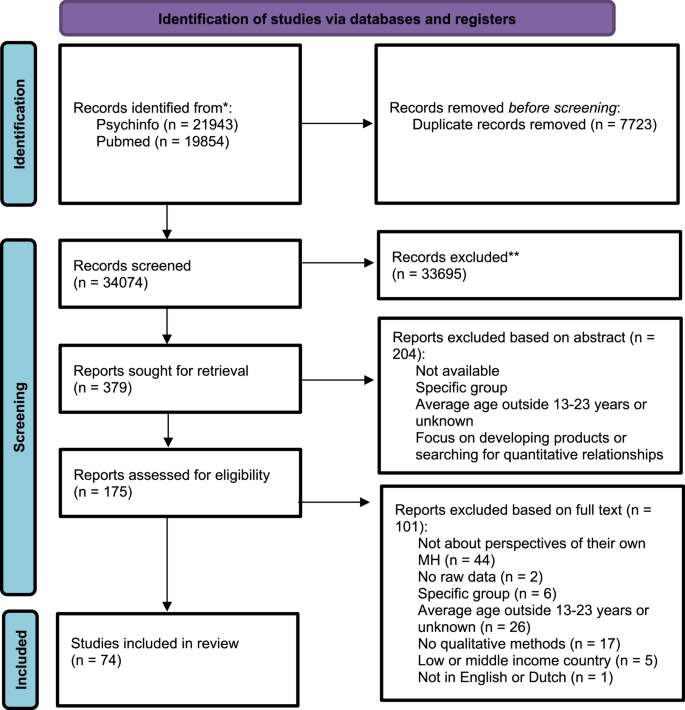

We searched in Pubmed and Psychinfo databases using terms including synonyms of adolescent, mental health or depression, perspectives and qualitative methods. A total of 34,074 records were screened for eligibility. Included articles were thematically analyzed in three stages: open coding, development of ‘descriptive themes’ and the generation of ‘analytical themes’.

Results

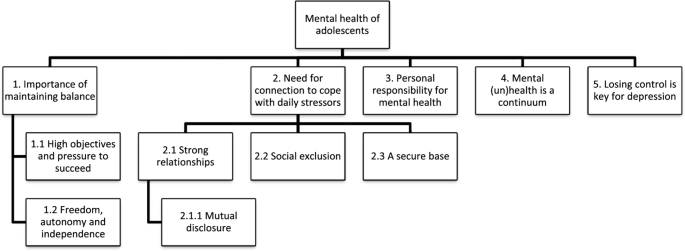

We found 74 articles eligible for the synthesis and identified five themes: (1) Importance of maintaining balance for positive mental health, (2) Need for connection with oneself and others to cope with daily stressors, (3) Personal responsibility for their mental health, (4) Mental (un)health is perceived as a continuum, (5) Losing control is key for depression.

Conclusion

This review provides a comprehensive exploration of the literature on adolescent’ perceptions on mental health and depression. Mental health issues are perceived as personal failure. Adolescents shoulder responsibility for their own mental health, while simultaneously expressing the need for social support. Recognizing adolescents’ active role presents opportunities for empowering interventions and support, it also amplifies the perceived burden of responsibility making them susceptible to depression. Our results suggest the need for systemic and collective interventions rather than solely individual-focused interventions. It is necessary to further study adolescents’ perceptions of mental health and depression, to promote their mental health, prevent mental health problems and stimulate seeking (professional) help when in need.

Peer Review reports

Background

The prevalence of mental health disorders among adolescents is substantial, with one in seven adolescents affected globally [1,2,3]. Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders among adolescents and is estimated to affect 8% of all adolescents [4]. On top of that, 34% of the adolescents report elevated depressive symptoms in self-questionnaires [4]. Three quarters of the first episodes of depression reveal before the age of 25 years [5]. Only half of the adolescents exhibiting depressive symptoms are identified during adolescence [6]. There is considerable unmet need for help or support among adolescents with mental health issues [7, 8]. When mental health issues go unrecognized and are improperly treated, an increased risk occurs of persistence into adulthood. Experiencing mental health issues can have detrimental consequences, affecting school or work performance, relationships with family and friends and the ability to engage in the community [9, 10]. In the long term, fewer life opportunities and decreased physical and mental health may be the result [2, 11,12,13,14]. The focus of this review is to give an overview of perspectives of adolescents on overall mental health, and in particular depression due to its high prevalence and the onset of symptoms during adolescence. Understanding adolescents’ perspectives on mental health and depression may help professionals working with this target group and may yield better policies for prevention of mental health issues and diagnosing and treating the mental health issues emerging in adolescence.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health is defined as the ability to connect, function, thrive and cope [15]. This aligns with the self-determination theory about motivation, declaring adolescents have three basic psychological needs, namely a feeling of autonomy, a feeling of competence and relating with others and the environment [16]. Fulfilling those needs are crucial for optimal development and mental health. The self-determination theory is one of the most used and studied theories in the psychological field [17] and provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the factors that contribute to mental health. Recent reviews on mental health of adolescents demonstrated the impact of personal characteristics and physical, social, socioeconomic and digital environments [18,19,20,21]. Social connectedness [22] and stress, mainly caused by schoolwork [23, 24], were significantly contributing to mental health issues. Overall, individual, social and structural factors collectively influence mental health. However, it is unknown what the perspectives of adolescents are about mental health, because knowledge is mostly based on surveys and questionnaires with predefined categories; adolescents were not able to use their own narratives. Qualitative methodology like interviews, focus groups and open-ended questions are more appropriate for this research question and gives adolescents a chance give their view in their own words.

Adolescence is a transitional phase between childhood and adulthood. The WHO defines an adolescent as an individual between 10 and 19 years of age; however, the prefrontal cortex continues to mature beyond this period, typically reaching full maturation around the age of 25 [25]. In this review, we define an adolescent as an individual between 13 and 23 years, because -based on our clinical experience- this range encompasses the developmental and social transitions that occur before individuals reach adulthood. During adolescence, social and emotional habits are developed which are important for mental health. Increased empathy and perspective taking, peer relationship building, and effective communication skills are examples of social habits. Emotional habits such as emotional regulation, self-awareness, stress management, resilience and self-reflection are improved during adolescence.

To understand how adolescents experience mental health issues, it is essential to consider the perspectives of adolescents on mental health and depression. A more profound understanding of the perspectives may improve mental health promotion, prevention and intervention strategies, fostering active engagement from adolescents in improving their own mental health. Success of mental health interventions depend on to which degree it aligns with individual’s own perspectives on mental health and depression. Furthermore, it can contribute to optimizing the organization of mental health care. Knowledge of perspectives of adolescents can optimize community and population-level interventions. In addition, gaining insights into adolescent perspectives can guide professionals in detecting potential mental health issues at an early stage. For instance, an improved understanding will assist professionals to understand which symptoms are taken for granted by adolescents and which symptoms are important and should be treated by mental health care professionals.

In this systematic review, we aim to give an overview of the perspectives on mental health and depression expressed by adolescents in high-income countries (HIC). We focus on high income countries because we hypothesize they share a similar societal structure regarding education and availability of mental health services. Furthermore, only 44% of adolescents in HIC receive mental health services for their mental health issues, which emphasizes the importance of more knowledge on adolescents’ perceptions [26]. This review gives an overview on how adolescents define mental health, along with an exploration on how they perceive their own mental health and when adolescents identify themselves with depression. Reviews including adolescents’ perspectives has primarily focused on wellbeing [21, 27] or help-seeking behavior in relation to mental health [8]. Adolescents in low or middle-income countries perceive wellbeing as multifactorial and influenced by developmental and cultural phases [8, 28], To the best of our knowledge, to date, no reviews have addressed adolescents’ perspectives on mental health and depression in high income countries.

Methods

This review was executed according to the guidelines of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis” (PRISMA) statement [29]. The review was registered on PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023390479).

Search strategy

The objectives of this study were to investigate the perspectives of adolescents on which factors are related to their own mental health, the definition of mental health and when they perceive mental health issues develop into depression. Two databases, PUBMED and PSYCHINFO, were systematically searched between May 2020 and August 2020 and updated August 2023. A search strategy was developed with the SPIDER tool (Appendix 1) [30]. In each component search terms were connected with ‘OR’ and across components with ‘AND’. No restrictions of time of publication and language were used.

Eligibility

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated collaboratively by all authors (Appendix 2). Studies were considered for inclusion if they met the following conditions: (1) the participants were adolescents, defined by an average age range of 13 and 23 years, (2) data were collected in high-income countries as defined by the World Bank [31], (3) studies used original data, (4) the research methodology incorporated qualitative approaches and if it was a mixed design, the outcomes of the qualitative component were reported separately, (5) the study outcomes focused on perspectives of adolescents on their own mental health or mental health issues, (6) they were published in either Dutch or English language.

Data screening

For article processing and identification, Endnote X9 was used. Records of the two databases were imported and duplicates were removed. The eligibility of titles was initially screened by a single researcher (EB), while abstract and full-text screenings were conducted independently by two researchers (EB, SR). In case of uncertainty, the article in question was discussed with other members of the research team until consensus was achieved. During the process, the research team convened regularly to discuss the progression and address any arising difficulties and challenges.

Data extraction

In our review, extracting ‘key concepts’ for analysis that would represent the article proved challenging. Furthermore, not all articles provided direct quotations from participants, but only paraphrases or summarizing themes. To address this, we used all the textual data reported under the ‘results’ section of the articles. Only results which were important to answer the research question were included in the analysis. All the articles were entered in MAXQDA for qualitative data analysis. We extracted primary data including publication, country, primary aim, setting (general population, residential, clinical), study sample, study design, methodological approaches.

Data analysis and synthesis

Thematic synthesis was employed for data analysis and was conducted in three phases: open coding of the text, development of ‘descriptive themes’ and the generation of ‘analytical themes’ [32]. This method ensures to stay close to the primary studies’ findings while producing new insights and hypotheses in a transparent manner. A pilot search preceded the initial search to establish a preliminary coding framework (EB). Upon including the articles of this review, we started with open coding of the results (EB). The research team then crafted an initial framework based on the open codes and the initial framework (EB, MH, SR). Descriptive themes were identified by studying the content of the separate codes and organized on a digital notebook (EB, MH, SR). Descriptive themes that were identified included ‘communication’ and ‘disclosure’ (Appendix 3). These descriptive themes served as the basis for forming analytical themes, which were subsequently organized into a diagram. For example, the descriptive themes ‘communication and disclosure’ were placed into a broader theme ‘connection’. Subthemes were identified and finalized. In the theme ‘connection’, we identified 4 subthemes: strong relationships, mutual disclosure, social exclusion and a secure base. After thorough analysis we found ‘mutual disclosure’ to be a sub-theme of strong relationships, as mutual disclosure was only possible for adolescents within a strong relationship. All authors were consulted to reach consensus. Data were systematically organized to align with our research question, aiming to understand the perspectives of adolescents on mental health and depression in HIC.

Quality assessment

All articles were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist [33], recommended for qualitative evidence syntheses. The CASP checklist comprises ten core questions to evaluate validity and effectiveness of the included studies. Assessment was done by two authors (EB, MH). The CASP recommends to only use the checklist to determine the steps, the strengths and limitations of studies, and to evaluate the credibility and meaning of the outcomes of studies. Therefore, we did not categorize quality of the studies into high, middle and low quality, neither did we exclude articles based on the results of the CASP checklist.

Results

Study characteristics

The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) describes the selection process. Table 1 shows all 74 included articles and summarizes aims, sample and study population, methods, findings and analytical themes. Several qualitative methodologies were used: 50 articles reported individual interviews, 26 articles focus groups, 4 articles written accounts and 5 articles participatory methods. Included articles studied participants globally: 35 studies included participants from Europe, 31 studies from Northern America, 1 study from Southern America, and 7 studies from Australia. A total of 3465 adolescents was included in 72 articles; the exact number is unknown because of missing data in 2 articles. Different study groups and settings were found: 48 articles included adolescents from the general population, 29 articles included adolescents in a clinical setting and 3 articles included adolescents in residential care.

PRISMA flow chart of the selection process. The outcomes of both searches were combined

We identified five themes from our thematic synthesis: (1) Importance of maintaining balance for positive mental health, (2) Need for connection with oneself and others to cope with daily stressors, (3) Personal responsibility for their mental health, (4) Mental (un)health is perceived as a continuum, (5) Losing control is key for depression. Themes and subthemes are shown in Fig. 2.

Themes and subthemes found in the review

Maintaining balance in order to have a positive mental health

Balance is a central theme for adolescents when talking about mental health and two subthemes were identified: ‘high objectives and pressure to succeed’ and ‘freedom, autonomy and independence’. The importance of balance is illustrated by: ‘Participants defined mental wellbeing as living a well-balanced life. A well-balanced life was described as key to nurturing pleasant emotions and involved having the following factors present in one’s life: Positive relationships with family; positive relationships with friends; a positive relationship with a girlfriend or partner; performing well on the field; successfully balancing any educational or employment responsibilities; and positive spiritual wellbeing. In short, when everything is going “pretty well”.’ [34]. Also, adolescents consider active involvement in order to experience emotional balance to live a well-balanced life, shown by: ‘Emotional balance was also identified as meaningful for wellbeing, and this factor appeared frequently under the designation “middle-ground”: “It takes a lot of willpower to achieve the middle-ground” (M., 17)’ [35]. The following paragraphs will elaborate on how balancing in order to achieve positive mental health relates to various topics.

High objectives and pressure to succeed: expectations and responsibility negatively impact mental health

Adolescents described high objectives and responsibility need to be balanced. They describe setting high objectives for future orientation to feel happy: ‘Being happy is related to academic success, career pathways, the right path and having a better life.’ [58]. Nevertheless, high objectives could also cause stress from pressure to succeed.

Pressure to succeed originated from adolescents themselves, but also from parents and teachers. Additional stress came with opposite social and cultural expectations; some adolescents explained the norms within their family house was different than the norms of the outside society. Being a role model for younger siblings was mentioned as a reason to do well. Girls claimed they had to work harder than boys to succeed in life, so they made higher demands to themselves. Responsibility is mainly felt by girls for situations at home, at school and during leisure time, while having difficulties in prioritizing. A low degree of responsibility gave the adolescents the freedom to obtain a better balance by not responding to all demands. Balance between responsibilities and self-chosen objectives helped adolescents to be mentally healthy.

Freedom, autonomy and responsibility: balancing between independence and parental inhibition

Being able to decide for yourself, to stay in control, freedom and independence are important for the mental health of adolescents, illustrated by: ‘Most participants indicated that being able to make their own choices and decisions in life enhances their quality of life because it helps them to take responsibility for their own actions. The ability to make their own decisions promotes a sense of self-agency and self-determination’ [97]. On the other hand, adolescents described how the responsibility which comes with freedom and independence can be a burden, shown by: ‘Responsibility was also experienced as burdensome and, thus, negative for mental health. This was most commonly exemplified by experiences reinforcing negative effects of social interaction and performance: ‘There is so much to take responsibility for. It can be hard if you have problems at home or in school’ [75].

Parental inhibition could hinder freedom and independence. Adolescents stated parents who balanced between control and freedom were considered good parents. An unclear degree of freedom on the other hand negatively influenced mental health. Adolescents believed coming of age and becoming independent were associated with freedom and thus better mental health. Older adolescents described how living away from their parents allowed them to develop life skills, social support networks, explore identity and build confidence.

Feeling connection with oneself and others is important in order to cope with daily stressors

Adolescents experience connection with others is particularly important because of the support they receive. Subthemes of connection are: ‘strong relationships’, ‘mutual disclosure’, ‘social exclusion’ and ‘a secure base’. Feeling connected prevents a person from feeling lonely: ‘Not having friends is a determinant of not feeling mentally well, according to the girls and the boys. If you do not have any friends you feel lonely, unhappy and bored’ [69]. Having good relationships with family and friends or peers provided love and support which helped them cope with daily stressors. In the following paragraphs, the subthemes with their relation to the mental health of adolescents are presented.

Strong relationships: supportive relationships and relatedness are important to feel good

Strong relationships provide support and give a sense of relatedness. Family, friends and teachers can form a strong relationship with adolescents. Pivotal for strong relationships are the following aspects: receiving support, encouragement, trust, honesty, respect, motivation, instruction, and not feeling judged. Family is for most adolescents a source of unconditional support. Boys described parents as the first source of support, while girls expressed their parents would not be able to understand certain matters and therefore turned to friends. Girls also expressed they would not talk to boys because they would not understand, and therefore they would turn to their mothers first before going to their fathers. Older adolescents valued siblings as supportive and valuable. If there was a negative family relationship, it could be compensated for by a supportive peer. Girls talked about having romantic relationships as the most important connection. Other types of connections were with a higher power, their culture and heritage, animals, a staff member or a coach. Relationships with teachers and school counselors could also give support when the bond gets strong, but many adolescents describe a lack of trust in teachers. Social restrictions of the COVID pandemic showed connection to others in real life were more important than talking digitally. Strong connections with others are not static because the relationships of adolescents are under continuous evaluation.

Furthermore, adolescents spoke about relatedness and group cohesion. Community groups or being part of a sports team could improve mental health: ‘Images of community groups (voluntary, youth and interest groups) were captured by several participants, and they all expressed the importance of connecting with others who can: ‘understand’ [48].

When adolescents experienced a breach in connection because of a conflict with family, peers or a dating partner, this negatively impacted their mental health, illustrated by: ‘Arguments or “drama” provoked stress: “When people (friends) close to me are fighting, it’s just stressful when it’s going on around me.”’ [90]. Adolescents expressed they feared conflicts because they did not know how to resolve them, leading to their escalation. Conflicts with a friend affected the ability to work at school. Conflicts with parents arose when they became over-involved in adolescents’ lives, but conflict between parents or family members also caused adolescents stress.

Mutual disclosure: supportive relationships encourage an adolescent to open up about real feelings

Strong relationships offer support, and a supportive connection was mainly associated with mutual disclosure. Mutual disclosure is important in order to have someone to talk to about personal issues or someone who is always there for you: ‘Most participants had methods for managing stress. Many sought support, comfort, advice, or the possibility of just ‘venting’ from someone with whom they had close emotional ties (81%). As one participant stated: “…talking or venting with friends or family to get it off of my chest. They offer advice and can help me work through a problem or disappointment.”’ [90].

Mutual disclosure was an essential part of supportive connections. Adolescents considered disclosure an effective strategy for mental health, even though adolescents tended to hide their feelings. Strong relationships caused adolescents and peers to open up more to discuss sensitive topics because adolescents believe the shared information will not be passed to others, illustrated by: ‘Adolescents described how trusting others was a prerequisite for sharing feelings and problems or seeking support in relations and networks, but also that trust was built through dialogue and sharing. Thus, sharing in this context was not about everyday topics or small talk, but about sensitive matters that were shared very selectively with others. To be able to confide in friends, parents or significant others, adolescents described certain expectations that needed to be met. For example, they spoke of the need to feel confident that the receiver(s) could keep a secret and not tell others’ [36]. Mutual sharing of personal information created a sense of trustworthiness and therefore teachers who share personal information are easier to open up to. Adolescents felt most secure within romantic relationships to express their real feelings. Also, they perceived gender differences; it is harder for boys to talk about mental health. We found a contradiction in how boys perceive their ability to talk about feeling and emotions; some boys stated they were confident in discussing feelings, while they also said expression of emotions in public was unacceptable and a risk factor for bullying. Fear of social exclusion was a reason to not disclose negative feelings for both boys and girls.

Social exclusion: lifelong negative consequences for adolescents

Social exclusion consisted of bullying and discrimination and adolescents describe social exclusion harmful for mental health: ‘Numerous participants said that they had been bullied at school, with severe and long-term consequences for their self-esteem and their ability to function in school or in work settings’ [67]. They believed the main reason for bullying was physical appearance and being an easy target because of personal characteristics.

The mental health of adolescents who faced discrimination decreased illustrated by: ‘The majority of participants, in the face of discrimination, reported experiencing a range of emotional reactions such as sadness, frustration, helplessness, embarrassment, and anger. Participants shared that these experiences of discrimination were stressful and impeded their sense of acceptance in mainstream society’ [100]. Girls talked about racism between their ethnic community, while boys talked about racism between their and other ethnic communities. Adolescents described being looked at differently and being treated differently was the main stressor of their lives, illustrated by: ‘For these young men, the “normal stress of life” was “not a big deal” and was “easy to deal with”, but “being Black in this society is always a stress that eats away at your soul”’ [72].

A secure base: home and school are the corner stone of mental health

Feelings of safety at home and at school are essential for good mental health. Adolescents describe home should be the secure base in life: 'Home conditions were consistently described by both girls and boys as a key factor influencing mental health. Several adolescents emphasized that feeling unhappy or unsafe at home can significantly impact one’s mental well-being. Some participants even equated mental health with the quality of the home environment. As one 13-year-old girl explained: “if your parents do not care about you, or if you do not get proper food, or if your parents beat you and so on.”’ [69]. Adolescents mentioned the following to influence the home environment: family problems, loss of a family member because of death or deportation, abuse or violence, divorce, self-parenting, overprotective parents and chaotic environments. Girls emphasized family factors more than boys. Problems at home could also affect other areas in life, like schoolwork. Change in the home situation because of moving to another place impacts social relations and networks and therefore impacts the mental health of adolescents.

Some adolescents consider school as their second home and therefore a stable school environment can also provide a secure base, shown by: ‘Most of the students described their school as a haven. Students titled a picture of their school for photovoice exhibit “Our Home Away from Home,” and described it as “a safe environment that’s like a second family” and “a place for peace of mind,” Some students like coming to school because they like the people around them’ [91]. Adolescents described school is important because of the presence of friends. Teachers are the adults within the school setting and therefore fulfill a different role in a positive and negative way. Some adolescents describe relationships with teachers offering support and emotional connection, while others described they do not trust teachers and they feel unable to receive assistance from teachers. Bullying was considered to happen mostly at school. Most stressful in school were tests and academic pressure. Social control and rules and penalties caused a feeling of lack of liberty. When school was disrupted during the COVID pandemic adolescents experienced less stress, because of less in-school difficulties and workload, while other described lower grades as a result of the school system during the COVID pandemic.

Adolescents perceive mental health is their own responsibility

Adolescents described mental health needs self-management and consider dealing with mental health issues their own responsibility: ‘Students talked about getting a handle on their feelings and making the decision to be calm and happy’ [91]. Feeling mentally unhealthy is perceived as failure, illustrated by: ‘The pressure they felt has to do with ideas that exist in the society about failing. A dominant idea was that when you cope with an issue in an efficient and proper way, the outcome will be good. This means also that you always have to know, and that you can know, how to cope with an issue. And if you are depressed, this means you have personally failed to cope’ [53].

An effective way to manage their mental health is positive thinking and maintaining physical health by exercising and healthy food. Other actions are ignoring thoughts or hiding symptoms, self-expression and being aware of triggers. A number of activities are mentioned which distract the mind and help you to think positively are music, reading, going outside, physical activity, social media, playing video and board games, spending time with peers, family or animals, but also being alone.

Mental (un)health is perceived as a continuum

Adolescents described mental health as how you feel inside and described a mental health continuum from positive mental health to negative mental health. Mental health issues are influencing someone’s mental health state, illustrated by: ‘The adolescents suggested that mental health is complex and cannot be described solely in terms of having mental health problems or not, indicating that good mental health and mental health problems are not opposite poles on a continuum. Moreover, they recognized a need to consider aspects of good mental health, as well as diagnoses and symptoms of mental health problems to establish an individual’s mental health state.’ [64]. Mental health is considered complex and influenced by interpersonal, intrapersonal and contextual dimensions. Adolescents recognized that different dimensions of mental health are interconnecting, illustrated by: ‘’feeling bad about yourself’ impacted relationships, school-work and other emotions, and the former was influenced by ‘pressure’, feeling tired, or a fight with a friend or family member’ [42]. Life phase and situation influenced which dimension of mental health predominates.

We found variation in the use of the term mental health issues, some adolescents refer to mental health disorders, while others refer to everyday problems: “most people at points in their life experience mental health problems” [86]. Adolescents described mental health as how you feel inside, which can be good or bad, shown by: ‘The adolescents perceived mental health as an emotional experience, which could be described as positive or negative. The emotions could be internal feelings or feelings towards other people’ [66]. Positive mental health is one side of the continuum and adolescents use positive mental health and mental wellbeing interchangeably. An adolescent describes positive mental health as: ‘Being able to laugh at yourself, being able to laugh with others, join in conversations and have input, waking up and not feeling like you just want to go back to bed and there’s no point in the day. Having positive mental health makes you seize the opportunity in each day even if it’s the smallest thing’ [60]. Negative mental health was more difficult to describe for adolescents: ‘The adolescents did not use the word ill-health or mental health problem, to them ‘feeling bad’ was part of mental health’ [69]. This statement emphasizes adolescents consider negative mental health different from mental health issues or a mental health disorder.

Mental health seems intangible and difficult to describe for adolescents, because of the lack of a visible problem: ‘With physical (health) problems it’s like you can’t walk, if you’ve got a limb missin’ or if you are in a wheelchair but if you have got a mental (health) problem, you are not really there, you are somewhere else, you can’t see it’ [52]. In particular younger adolescents find it difficult to articulate the concept of mental health, while older adolescents have become more aware of the concept and are able to give examples. One study [69] reported differences between age groups: when asked about mental health, younger adolescents described relations with friends and family, while older adolescents described their feelings. Also, some adolescents described the importance of mental health literacy by highlighting that mental health is not recognized as an important concept in their culture of origin, as illustrated by the following quote from a participant in the UK originally from Ghana: ‘Yeah honestly, I didn’t think I could have mental health issues. Cause like in Ghana, you aren’t educated about mental health issues so you don’t really know that it is a thing…So it’s like, I didn’t think I could have it’ (Sam)’ [83].

Depression starts with the experience of losing control

We found that adolescents consider depression as a state of being where the adolescents feel out of control. Adolescents explain how during years the distress builds up and how they normalize their symptoms by talking with others and comparing their experiences. Then they describe a mental tipping point, where external stressors increasingly stretch one’s mental and emotional resources because of the duration and weight and adolescents feel they lose control, illustrated by: ‘This feeling of being out of control was seen as a critical antecedent to the onset of depression; for example P25 spoke of “being overwhelmed by something that you feel like you have no control over”’ [46]. Sometimes a series of difficulties is prior to the mental tipping point, sometimes a single event and sometimes the cause is not known.

When things get out of control adolescents experience a disconnection from others which is the main problem of having depression according to adolescents, show by: ‘Anne-Marie (age 17) described what she thinks of when she hears the word ‘depression’: I think somebody just sitting alone. Not like they’d feel like they were close to anyone. And like feeling depression, they just, they feel all alone… That’s what I think when I hear the word. Somebody that’s alone’ [65]. Many adolescents reasoned disconnection was the origin of depression, explained by: ‘Lack of friends or damaging experiences with peers were often seen as having contributed to or even being a sole reason for the development of depression’ [67]. On the other hand adolescents described depression caused social withdrawal. Social withdrawal could be intentional but could also be as the result of depressive feelings. A supportive network of friends and family can prevent depression. Adolescents also mentioned other causes of depression: intrapersonal, social, environmental, biological and traumatic events. Interestingly they claimed biological causes are not a cause, but a trigger.

Quality appraisal

Methodological robustness showed variability across all studies according to the assessment using the CASP checklist [33] (Appendix 4). All eligible articles scored positive on clear aims (CASP item 1). Most articles scored positive on a clear research design, an appropriate methodology, an appropriate data collection and ethical considerations, while for a few articles this was unclear (CASP items 2, 3, 5 and 7). Articles with methodological issues scored negative and were found relating to ambiguous or unsuitable recruitment strategy, data analysis, clear results and a contributing discussion (CASP items 4, 8, 9 and 10). Almost all of the articles scored negative on considering the relationship between the researcher and the participants.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we explored adolescents’ perspectives on mental health and depression. We focused on understanding how adolescents in high-income countries define mental health, pinpointing themes crucial for their mental health and identifying when they associate themselves with depression. To our knowledge, this is the first review of its kind focusing on qualitative data from high-income countries. Our findings suggest that adolescents primarily perceive mental health and depression through the lenses of balance and connection. Subthemes include ‘high objectives and pressure to succeed’, ‘freedom, autonomy and independence’, ‘strong relationships’, ‘mutual disclosure’, ‘social exclusion’ and ‘a secure base’. Adolescents shoulder a lot of responsibility for their own mental health, viewing it as a continuum ranging from positive mental health to negative mental health states. Depression is perceived to begin when distressed feelings spiral out of control.

Our research highlighted the significance of connection and balance as pivotal themes, influencing the mental health of adolescents. Furthermore, we identified several subthemes in this review. These themes align with the principles of the self-determination theory, which emphasizes autonomy, competence and relatedness and provides a valuable framework for understanding the findings [16]. Particularly, the subtheme ‘freedom, autonomy and independence’ underscore the adolescents’ desire for personal agency -the liberty to make their own choices, reflecting the need for autonomy. Autonomy proves most beneficial within a context that is both secure and supportive, indicating that while adolescents seek independence, they thrive in environments that offer stability and encouragement. The subtheme ‘a secure base’ emphasizes the critical need for a stable and secure foundation, enabling adolescents to successfully navigate the challenges of autonomy and independence. We found girls emphasized family factors more than boys. This outcome might be connected with our observation that girls express more responsibilities, also at home. The importance of competence is shown by the subtheme ‘high objectives and pressure to succeed’, underscoring the necessity of balancing between challenging tasks and personal development. Furthermore, ‘strong relationships’ and ‘mutual disclosure’ aligns with relatedness. Positive relationships, characterized by open communication and relatedness, are essential for positive mental health and the fulfilling basis psychological needs.

The findings align with previous reviews on mental health and wellbeing, which did not specifically include the perspectives of adolescents. The importance of family support [20, 108, 109] and social connectedness [22] has been previously acknowledged in the literature. Furthermore, issues such as balancing responsibilities [23], social exclusion [110,111,112,113] and an unstable home environment [114, 115] have been discussed in relation to adolescent mental health. Unlike existing literature, our review finds adolescents think self-disclosure to be beneficial to improve adolescents’ mental health, while in the literature self-disclosure was only found to be effective when an adolescent was having depression [116]. There are different types of self-disclosure studied in the literature. This might explain different outcomes. In our review we focused on self-disclosure among friends, family or teachers in a personal setting. Other types of self-disclosure are self-disclosure during intervention at school in groups. Additionally, while academic pressure, associated with setting high objectives, is often viewed as detrimental to mental health [23, 117], our findings indicate that such objectives and pressure to succeed can motivate adolescents towards a better future.

We found adolescents assume responsibility for their own mental, leading to perceptions of poor mental health as personal failure. The sense of responsibility reflects the cultural norms of neo-liberal societies, such as those in high income countries, where individual accountability and self-governance are highly valued [118]. In such societies, the emphasis on personal agency and self-determination has likely contributed to adolescents internalizing the idea that maintaining good mental health is within their control. While this can empower adolescents by encouraging them to take active steps towards maintaining their mental health, it also imposes a significant burden on them. When adolescents face mental health challenges, this responsibility can translate into feelings of failure, perpetuating the stigma associated with poor mental health.

Adolescents conceptualize mental health as a continuum, with depression seen as a distinct state characterized by a perceived loss of control. Remarkably, adolescents contend depression can exist simultaneously with aspects of positive mental health, emphasizing the potential for its management through effective strategies. These perspectives align with the dual factor model of mental health [119], which considers both indicators of positive subjective wellbeing and the presence of psychopathological symptoms. This review highlights that the presence of depression does not equate to poor mental health overall. The findings indicate that adolescents often discuss mental health in terms of emotions, and it’s important to note that we believe adolescents refer to daily functioning when they talk about depression. This perspective is further validated by adolescents’ descriptions as a state of being out of control, directly relating to their daily functioning. Therefore, early detection for mental health issues and depression should extend beyond merely identifying symptoms of depression to also on recognizing the absence of positive mental health indicators. For instance, an adolescent feeling overwhelmed by family issues may face potential mental health concerns, even if they do not exhibit classic symptoms of depression. Solely focusing on the symptoms of depression could result in such an adolescent not receiving the necessary support. Consequently, mental health prevention efforts should emphasize the promotion and support of positive mental health as a priority.

Adolescents’ experiences with depression are closely linked to a profound a sense of losing control, earlier research on adult depression described this before [120, 121]. This aspect of losing control emerges as a critical factor for the onset of the depressive symptoms. The interaction among of autonomy, expectations and the norm of maintaining a positive mental health, creates a complex scenario for adolescents. The expectation for adolescents to be accountable for their mental wellbeing, introduces an additional complexity to this situation, where the dread of failure and societal scrutiny can amplify the feelings of helplessness. Hence, adolescents might normalize their symptoms until they encounter a juncture (referred to as the ‘mental tipping point’), at which they can no longer deny their depressive state. The experience of feeling out of control emerges as a significant indicator for the onset of depressive episodes among adolescents. Acknowledging this dynamic is essential for developing targeted inventions aimed at the early identification, support, and destigmatizing of mental health struggles among adolescents.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review outlines the perspectives of adolescents on mental health and related conditions in HIC, utilizing a comprehensive search strategy developed in collaboration with an experienced health literature librarian. A broad array of terms was employed to ensure no significant articles were overlooked. Despite identifying a large number of articles, we applied systematic review methodologies to maintain the integrity of our synthesis. A notable limitation encountered was the heterogeneity of the final set of studies included. Different age groups, study designs and outcomes were included. The lack of access to raw data made the analysis complicated. The decision to focus exclusively on HICs was based on the assumption of a similar societal structure with regard to education and availability of mental health services, which may introduce bias due to differences in and access to health care systems, such as those between the US and Europe. Also, we excluded well-defined risk groups such as LGTBQ and maltreated youth, which can influence generalizability and transferability. Few articles critically discussed the role of the researcher and potential biases, and none within our synthesis addressed cultural differences within the country. This lack of consideration for intra-country cultural differences represents a significant gap in the literature, impacting the depth and breadth of our synthesis.

Implications

The findings of this review carry significant implications for the field. Adolescents take considerable responsibility for their mental health, underscoring the need for a nuanced approach in addressing mental health, balancing the promotion of personal agency with the external factors that may contribute to mental health issues. This approach should balance the promotion of personal agency with the recognition of external factors that contribute to mental health. Shifting from the individual-focused “i-frame” to the systemic “s-frame” will redirect the focus from individual interventions to system-level changes, thereby fostering positive mental health. A system-level change should include the creation of an inclusive society, fostering a safe haven for adolescents both at home and in school. Furthermore, the results underscore the significance of feeling connected and balanced. Mutual disclosure emerges as a crucial facilitator, providing adolescents with a heightened sense of safety to articulate their mental health concerns. This is significantly relevant for (mental health) professionals, as well as for educational professionals. Teachers can significantly influence the lives of adolescents by creating a secure environment and establishing a strong connection. The impact of such relationships is particularly profound when teachers have personal experiences related to mental health that they can share, thus enhancing their ability to support their students [122]. Moreover, the findings reveal that adolescents often hide their distress, attempting to treat their feelings as normal. The role of friends and family emerges as crucial due to the social support they provide. Despite the significant importance of social support when experiencing mental health issues, only one of four adolescents actively seeks increased social support during such circumstances [123]. Consequently, integrating family and social networks into the treatment of mental health issues is essential. Additionally, there is a critical need to educate adolescents about mental health, facilitating mutual support and encouraging timely referral to mental health professionals when necessary.

Future studies

Further research is crucial for understanding how adolescents experience the mental tipping point leading to depression and to gain deeper understandings of the position of depression within overall mental health. It’s vital to comprehend adolescents’ perspectives on the most effective prevention methods, as current strategies do not adequately reach all adolescents, particularly marginalized ones who may be most in need of support [124]. Furthermore, more research should be done on perspectives on mental health and depression in different development stages, since we found differences in explanations of mental health in younger and older age groups. Even though we claim interventions should shift towards system level change, future studies should also examine the perspectives of adolescents on interventions at the individual level. Wearables could be key in this personalized approach to prevention, leveraging the widespread use of mobile phones among adolescents, which generate extensive data. Additionally, it’s important to explore educational strategies that resonate with adolescents. Adolescents will only internalize the information if they feel accepted and taken seriously. Participatory research, as a method, offers a means to explore these topics further and empowers adolescents by giving them a voice and the opportunity to influence their own lives.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review provides an in-depth exploration of adolescent perceptions of mental health, highlighting the necessity for a systemic approach to address adolescent mental health issues. Our synthesis demonstrates that mental health prevention efforts should prioritize the promotion of positive mental health. Furthermore, recognizing adolescents’ proactive role in managing their mental health presents valuable opportunities for empowerment and support. There is a pressing need for further research to investigate how adolescents perceive subthreshold depression symptoms and the ways in which professionals can assist them before they reach a critical tipping point in their mental health.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

High income countries

MH:Mental health

UK:United Kingdom

WHO:World Health Organization

References

UNICEF. Ensuring mental health and well-being in an adolescent’s formative years can foster a better transition from childhood to adulthood. 2022. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/mental-health/. Accessed 24 Oct 2022.

World Health Organisation. Mental Health. 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed 24 Oct 2022.

World Health Organisation. Mental health of adolescents. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health2024.

Shorey N, Wong CH. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):287–305.

Google Scholar

Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Üstün TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–64.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ryan ND. Treatment of depression in children and adolescents. The Lancet. 2005;366(9489):933–40.

Google Scholar

Collishaw S. Annual research review: secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(3):370–93.

PubMed Google Scholar

Aguirre Velasco A, Cruz ISS, Billings J, Jimenez M, Rowe S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):293.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fergusson W. Mental Health, Educational, and Social Role Outcomes of Adolescents With Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(3):225–31.

PubMed Google Scholar

Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. The Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–13.

Google Scholar

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(1):66–72.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kinnunen L, Kylmä J. Associations between psychosomatic symptoms in adolescence and mental health symptoms in early adulthood. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16(1):43–50.

PubMed Google Scholar

Johnson D, Dupuis G, Piche J, Clayborne Z, Colman I. Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: A systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(8):700–16.

PubMed Google Scholar

Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Adult Functional Outcomes of Common Childhood Psychiatric Problems: A Prospective. Longitudinal Study JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(9):892–9.

PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. World Mental Health report. Transforming mental health for all. 2022.

Ryan D. Self-determination theory. Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. 2017.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Chapter Four - Brick by Brick: The Origins, Development, and Future of Self-Determination Theory. In: Elliot AJ, editor. Advances in Motivation Science. 6: Elsevier; 2019. p. 111 − 56.

Basu B. Impact of environmental factors on mental health of children and adolescents: A systematic review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119.

Rincon Uribe FA, Neira Espejo CA, Pedroso JDS. The role of optimism in adolescent mental health: a systematic review. J Happiness Stud. 2022;23(2):815–45.

Google Scholar

Scully M. Fitzgerald, The relationship between adverse childhood experiences, family functioning, and mental health problems among children and adolescents: A systematic review. J Family Ther. 2020;42(2):291–316.

Google Scholar

Aldridge M. The relationships between school climate and adolescent mental health and wellbeing: A systematic literature review. Int J Educ Res. 2018;88:121–45.

Google Scholar

Diendorfer T, Seidl L, Mitic M, Mittmann G, Woodcock K, Schrank B. Determinants of social connectedness in children and early adolescents with mental disorder: A systematic literature review. Dev Rev. 2021;60.

Kleinjan M, Pieper I, Stevens G, Van de Klundert N, Rombouts M, Boer M, et al. Geluk onder druk?: Onderzoek naar het mentaal welbevinden van jongeren in Nederland. 2020.

Anniko B, Tillfors M. Sources of stress and worry in the development of stress-related mental health problems: A longitudinal investigation from early-to mid-adolescence. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2019;32(2):155–67.

PubMed Google Scholar

Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449–61.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Barican JL, Yung D, Schwartz C, Zheng Y, Georgiades K, Waddell C. Prevalence of childhood mental disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis to inform policymaking. Evid Based Ment Health. 2022;25(1):36–44.

PubMed Google Scholar

Courtwright FM, Jones J. Emotional wellbeing in youth: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum. 2020;55(2):106–17.

PubMed Google Scholar

Renwick L, Pedley R, Johnson I, Bell V, Lovell K, Bee P, et al. Conceptualisations of positive mental health and wellbeing among children and adolescents in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Health Expectations. 2022;25(1):61–79.

PubMed Google Scholar

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):1–11.

Google Scholar

Cooke S, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

PubMed Google Scholar

Bank W. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021. Accessed: 25-11-2020 2020.

Thomas H. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10.

Google Scholar

Programme CAS. CASP ( Qualitative) Checklist. [online] Available at: CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (casp-uk.net). Accessed: 24-10-2022 2018.

Marsters C, Tiatia-Seath J. Young Pacific male rugby players’ perceptions and experiences of mental wellbeing. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(4):83.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cruz N, Sampaio D. Adolescents’ maps about well-being, distress and selfdestructive trajectories: What’s in their voices? Psychologica. 2016;59(1):95–115.

Google Scholar

Ahlborg MG, Nygren JM, Svedberg P. Social capital in relation to mental health—The voices of adolescents in Sweden. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(13):6223.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Alfaro J, Carrillo G, Aspillaga C, Villarroel A, Varela J. Well-being, school and age, from the understandings of Chilean children. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2023;144:106739.

Google Scholar

Anttila K, Anttila M, Kurki M, Hätönen H, Marttunen M, Välimäki M. Concerns and hopes among adolescents attending adolescent psychiatric outpatient clinics. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2015;20(2):81–8.

Google Scholar

Arsenault CL, Domene JF. Promoting Mental Health: The Experiences of Youth in Residential Care. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy. 2018;52(1).

Baumann SE, Kameg BN, Wiltrout CT, Murdoch D, Pelcher L, Burke JG. Visualizing mental health through the lens of Pittsburgh youth: a collaborative filmmaking study during COVID-19. Health Promot Pract. 2024;25(3):368–82.

PubMed Google Scholar

Blaskova LJ, McLellan R. Young people’s perceptions of wellbeing: The importance of peer relationships in Slovak schools. Int J School Educ Psychol. 2018;6(4):279–91.

Bourke L, Geldens PM. Subjective wellbeing and its meaning for young people in a rural Australian center. Soc Indicators Res. 2007;82(1):165–87.

Google Scholar

Brawner BM. Attitudes and beliefs regarding depression, HIV/AIDS, and HIV risk-related sexual behaviors among clinically depressed African American adolescent females. Arch Psychiatric nnurs. 2012;26(6):464–76.

Google Scholar

Breland-Noble AM, Burriss A, Poole HK. Engaging depressed African American adolescents in treatment: Lessons from the AAKOMA PROJECT. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(8):868–79.

PubMed Google Scholar

Brooks E, Dallos R. Exploring young women’s understandings of the development of difficulties: A narrative biographical analysis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;14(1):101–15.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cairns KE, Yap MB, Rossetto A, Pilkington PD, Jorm AF. Exploring adolescents’ causal beliefs about depression: A qualitative study with implications for prevention. Mental Health Prevent. 2018;12:55–61.

Google Scholar

Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Factors that influence mental health stigma among 8th grade adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:763–74.

Google Scholar

Charles F. Exploring young people’s experiences and perceptions of mental health and well-being using photography. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2020;25(1):13–20.

PubMed Google Scholar

Charman D, Harms C, Myles-Pallister J. Help and e-help: Young people’s perspectives of mental healthcare. Australian Family Physician. 2010;39(9):663–5.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chisholm K, Patterson P, Greenfield S, Turner E, Birchwood M. Adolescent construction of mental illness: implication for engagement and treatment. Early Intervent Psychiatry. 2018;12(4):626–36.

Google Scholar

Cocking C, Sherriff N, Aranda K, Zeeman L. Exploring young people’s emotional well-being and resilience in educational contexts: a resilient space? Health. 2020;24(3):241–58.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cogan R, Mayes G. The understanding and experiences of children affected by parental mental health problems: a qualitative study. Qual Res Psychol. 2005;2(1):47–66.

Google Scholar

De Mol J, D’Alcantara A, Cresti B. Agency of depressed adolescents: Embodiment and social representations. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2018;13(sup1):1564516.

Dewa LH, Lavelle M, Pickles K, Kalorkoti C, Jaques J, Pappa S, et al. Young adults’ perceptions of using wearables, social media and other technologies to detect worsening mental health: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(9).

Farmer TJ. The experience of major depression: adolescents’perspectives. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2002;23(6):567–85.

Google Scholar

Ferguson KN, Coen SE, Tobin D, Martin G, Seabrook JA, Gilliland JA. The mental well-being and coping strategies of Canadian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative, cross-sectional study. Can Med Assoc Open Access J. 2021;9(4):E1013–20.

Fornos LB, Seguin Mika V, Bayles B, Serrano AC, Jimenez RL, Villarreal R. A qualitative study of Mexican American adolescents and depression. J School Health. 2005;75(5):162–70.

Forrest-Bank SS, Nicotera N, Anthony EK, Jenson JM. Finding their Way: Perceptions of risk, resilience, and positive youth development among adolescents and young adults from public housing neighborhoods. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;55:147–58.

Google Scholar

Garcia C, Lindgren S. “Life grows between the rocks”: Latino adolescents’ and parents’ perspectives on mental health stressors. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(2):148–62.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hall M, Hyett N. Youth perceptions of positive mental health. Brit J Occupation Ther. 2016;79(8):475–83.

Google Scholar

Hannor-Walker T, Bohecker L, Ricks L, Kitchens S. Experiences of Black Adolescents With Depression in Rural Communities. Professional Counselor. 2020;10(2):285–300.

Google Scholar

Haraldsson K, Lindgren EC, Mattsson B, Fridlund B, Marklund B. Adolescent girls’ experiences of underlying social processes triggering stress in their everyday life: a grounded theory study. Stress Health. 2011;27(2):e61–70.

PubMed Google Scholar

Helseth S, Misvær N. Adolescents’ perceptions of quality of life: what it is and what matters. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(9–10):1454–61.

PubMed Google Scholar

Hermann V, Durbeej N, Karlsson AC, Sarkadi A. ‘Feeling down one evening doesn’t count as having mental health problems’-Swedish adolescents’ conceptual views of mental health. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(8):2886–99.

PubMed Google Scholar

Hetherington S. The theme of disconnection in adolescent girls’ understanding of depression. J Adolesc. 2002;25(6):619–29.

PubMed Google Scholar

Islam F, Multani A, Hynie M, Shakya Y, McKenzie K. Mental health of South Asian youth in Peel Region, Toronto, Canada: a qualitative study of determinants, coping strategies and service access. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11).

Issakainen H. Young people’s narratives of depression. J Youth Stud. 2015;19(2):237–50.

Google Scholar

Jenkins EK, Johnson JL, Bungay V, Kothari A, Saewyc EM. Divided and disconnected—An examination of youths’ experiences with emotional distress within the context of their everyday lives. Health Place. 2015;35:105–12.

Johansson B, Eriksson C. Adolescent girls’ and boys’ perceptions of mental health. J Youth Stud. 2007;10(2):183–202.

Google Scholar

Joronen K, Åstedt-Kurki P. Familial contribution to adolescent subjective well-being. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005;11(3):125–33.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kendal S, Keeley P, Callery P. Young people’s preferences for emotional well-being support in high school—A focus group study. J Child Adoles Psychiatric Nurs. 2011;24(4):245–53.

Kendrick A, Moore B. Perceptions of depression among young African American men. 2007.

Kral MJ, Salusky I, Inuksuk P, Angutimarik L, Tulugardjuk N. Tunngajuq: Stress and resilience among Inuit youth in Nunavut Canada. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2014;51(5):673–92.

PubMed Google Scholar

Lachal J, Speranza M, Schmitt A, Spodenkiewicz M, Falissard B, Moro M-R, et al. Depression in adolescence: from qualitative research to measurement. Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;2(4):296–308.

Google Scholar

Landstedt E, Asplund K, Gillander Gådin K. Understanding adolescent mental health: the influence of social processes, doing gender and gendered power relations. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(7):962–78.

PubMed Google Scholar

Larsson M, Johansson Sundler A, Ekebergh M. The influence of living conditions on adolescent girls’ health. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2012;7(1):19059.

Google Scholar

Larsson M, Sundler AJ, Ekebergh M. Beyond self-rated health: the adolescent girl’s lived experience of health in Sweden. J School Nurs. 2013;29(1):71–9.

Google Scholar

Lenoir R, Wong KK-Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people from black and mixed ethnic groups’ mental health in West London: a qualitative study. BMJ open. 2023;13(5).

Lieberman JT, Valdez CR, Pintor JK, Weisz P, Carroll-Scott A, Wagner K, et al. “It felt like hitting rock bottom”: A qualitative exploration of the mental health impacts of immigration enforcement and discrimination on US-citizen, Mexican children. Latino Studies. 2023:1–25.

Liu JL, Wang C, Do KA, Bali D. Asian American adolescents’ mental health literacy and beliefs about helpful strategies to address mental health challenges at school. Psychol Schools. 2022;59(10):2062–84.

Google Scholar

Lys C. Exploring coping strategies and mental health support systems among female youth in the Northwest Territories using body mapping. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1466604.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Matthews N, Kilgour L, Christian P, Mori K, Hill DM. Understanding, evidencing, and promoting adolescent well-being: An emerging agenda for schools. Youth Society. 2015;47(5):659–83.

Google Scholar

Meechan J, Hanna P. Understandings of mental health and support for Black male adolescents living in the UK. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;129.

Midgley N, Parkinson S, Holmes J, Stapley E, Eatough V, Target M. Beyond a diagnosis: The experience of depression among clinically-referred adolescents. J Adolesc. 2015;44:269–79.

PubMed Google Scholar

Midgley N, Parkinson S, Holmes J, Stapley E, Eatough V, Target M. “Did I bring it on myself?” An exploratory study of the beliefs that adolescents referred to mental health services have about the causes of their depression. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26:25–34.

PubMed Google Scholar

Moreton G. University students’ views on the impact of Instagram on mental wellbeing: a qualitative study. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):45.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Munson MR, Narendorf SC, Ben-David S, Cole A. A mixed-methods investigation into the perspectives on mental health and professional treatment among former system youth with mood disorders. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(1):52.

PubMed Google Scholar

Navarro D, Montserrat C, Malo S, Gonzàlez M, Casas F, Crous G. Subjective well-being: What do adolescents say? Child Fam Soc Work. 2017;22(1):175–84.

Google Scholar

O’Higgins S, Sixsmith J, Gabhainn SN. Adolescents’ perceptions of the words “health” and “happy.” Health Educ. 2010;110(5):367–81.

Google Scholar

Phillips R, Zelek B. Stresses, strengths and resilience in adolescents: a qualitative study. J Prim Prev. 2019;40:631–42.

PubMed Google Scholar

Rose T, Shdaimah C, de Tablan D, Sharpe TL. Exploring wellbeing and agency among urban youth through photovoice. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;67:114–22.

Google Scholar

Secker J, Armstrong C, Hill M. Young people’s understanding of mental illness. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(6):729–39.

PubMed Google Scholar

Stafford AM, Aalsma MC, Bigatti SM, Oruche UM, Draucker CB. 4 Getting A Grip On My Depression: A Grounded Theory Explaining How Latina Adolescents Experience, Self-Manage, And Seek Treatment For Depressive Symptoms. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(2):S2–3.

Google Scholar

Stafford AM, Bigatti SM, Draucker CB. Cultural stressors experienced by young Latinas with depressive symptoms living in a tumultuous sociopolitical climate in the United States. Arch Psychiatric Nurs. 2019;33(5):36–42.

Google Scholar

Stewart TM, Fry D, Wilson J, McAra L, Hamilton S, King A, et al. Adolescent Mental Health Priorities During the Covid-19 Pandemic. School Mental Health. 2023;15(1):247–59.

PubMed Google Scholar

Swann C, Telenta J, Draper G, Liddle S, Fogarty A, Hurley D, et al. Youth sport as a context for supporting mental health: Adolescent male perspectives. Psychol Sport Exercise. 2018;35:55–64.

Google Scholar

Swerts C, De Maeyer J, Lombardi M, Waterschoot I, Vanderplasschen W, Claes C. “You Shouldn’t Look at Us Strangely”: An Exploratory Study on Personal Perspectives on Quality of Life of Adolescents with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Residential Youth Care. Appl Res Qual Life. 2017;14(4):867–89.

Google Scholar

Terrizzi DA, Khan HA, Paulson A, Abuwalla Z, Solis N, Bolotin M, et al. Understanding Adolescent Expressions of Sadness: A Qualitative Exploration. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2020;34(4):321–39.

PubMed Google Scholar

Teng E, Crabb S, Winefield H, Venning A. Crying wolf? Australian adolescents’ perceptions of the ambiguity of visible indicators of mental health and authenticity of mental illness. Qual Res Psychol. 2017;14(2):171–99.

Google Scholar

Tummala-Narra D, Kaur J. South Asian adolescents’ experiences of acculturative stress and coping. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86(2):194–211.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ungar M, Brown M, Liebenberg L, Cheung M, Levine K. Distinguishing differences in pathways to resilience among Canadian youth. Can J Commun Mental Health. 2008;27(1):1–13.

Google Scholar

Vélez-Grau C. Using photovoice to examine adolescents’ experiences receiving mental health services in the United States. Health Promotion Int. 2019;34(5):912–20.

Google Scholar

Volstad C, Hughes J, Jakubec SL, Flessati S, Jackson L, Martin-Misener R. “You have to be okay with okay”: experiences of flourishing among university students transitioning directly from high school. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2020;15(1):1834259.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Weitkamp K, Klein E, Midgley N. The experience of depression: a qualitative study of adolescents with depression entering psychotherapy. Global Qual Nurs Res. 2016;3:2333393616649548.

Google Scholar

Wisdom JP, Agnor C. Family heritage and depression guides: Family and peer views influence adolescent attitudes about depression. J Adolesc. 2007;30(2):333–46.

PubMed Google Scholar

Wisdom JP, Green CA. “Being in a funk”: Teens’ efforts to understand their depressive experiences. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(9):1227–38.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Woodgate RL. Living in the shadow of fear: adolescents’ lived experience of depression. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):261–9.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Toumbourou JW, Lubman DI. Parent and family factors associated with service use by young people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Early Intervent Psychiatry. 2015;9(6):433–46.

Google Scholar

Pinto ACS, Luna IT, Sivla AdA, Pinheiro PNdC, Braga VAB, Souza ÂMA. Risk factors associated with mental health issues in adolescents: a integrative review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2014;48:555 − 64.

Malone P, Osman A. The general belongingness scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness. Personal Individual Diff. 2012;52(3):311–6.

Google Scholar

Alink C, Kim j, Rogosch FA. Mediating and moderating processes in the relation between maltreatment and psychopathology: Mother-child relationship quality and emotion regulation. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 2009;37(6):831 − 43.

Arslan A, Tanhan A. School bullying, mental health, and wellbeing in adolescents: Mediating impact of positive psychological orientations. Child Indicators Res. 2021;14(3):1007–26.

Google Scholar

Arseneault B, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems:‘Much ado about nothing’? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):717–29.

PubMed Google Scholar

Deb S, McGirr K, Bhattacharya B, Sun J. Role of home environment, parental care, parents’ personality and their relationship to adolescent mental health. J Psychol Psychother. 2015;5:6.

Google Scholar

Basu S, Banerjee B. Impact of environmental factors on mental health of children and adolescents: A systematic review. Children Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105515.

Gonsalves PP, Nair R, Roy M, Pal S, Michelson D. A Systematic Review and Lived Experience Synthesis of Self-disclosure as an Active Ingredient in Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults with Anxiety and Depression. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2023:1–18.

Steare T, Muñoz CG, Sullivan A, Lewis G. The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review. J Affective Disord. 2023;339:302–17.

Google Scholar

Lakeman R. Paradoxes of personal responsibility in mental health care. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2016;37(12):929–33.

Google Scholar

Keyes CL. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American psychologist. 2007;62(2):95.

PubMed Google Scholar

Heifner C. The male experience of depression. Perspect Psychiatric Care. 1997;33(2):10–8.

Google Scholar

Cornford H. Reilly, How patients with depressive symptoms view their condition: a qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):358–64.

PubMed Google Scholar

Happell B, O’Donovan A, Sharrock J, Warner T, Gordon S. Understanding the impact of expert by experience roles in mental health education. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;111:105324.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ng E, Weisz JR. Assessing fit between evidence-based psychotherapies for youth depression and real-life coping in early adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45(6):732–48.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J PsychiatrY. 2002;159(9):1548–55.

PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

Linda Schoonmade conducted the Pubmed and Psychinfo search and removed duplicates. This research was performed partly as an project of the medical specialist training for public health at the NSPOH.

Funding

No external funding for this study was given.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beket, E.S., Hoogsteder, M.H., Popma, A. et al. Perceptions on mental health and depression by adolescents, a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Public Health 25, 2911 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23638-8

Download citation

Received: 29 April 2024

Accepted: 17 June 2025

Published: 25 August 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23638-8

5 months ago

5 months ago

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  Indonesian (ID) ·

Indonesian (ID) ·